however, this level of detail is unnecessary to our conceptual understanding of how stellar

masses are meausured. Such a conceptual understanding can be conveyed with this small

power point visualization (you must be used to these by now).

however, this level of detail is unnecessary to our conceptual understanding of how stellar

masses are meausured. Such a conceptual understanding can be conveyed with this small

power point visualization (you must be used to these by now).

Approximately 50% of all stars are born in binary pairs (the physical reasons why this binary frequency is so large are unclear but its probably related to the same kind of formation properties that produce solar systems about stars). We will study the star formation process later in this class, for now, however, we want to take advantage of the fact that binary stars offer the only viable means for directly measuring stellar masses

The Mathematical Details of how one uses

Newton's and Kepler's laws to derive stellar masses are shown here.  however, this level of detail is unnecessary to our conceptual understanding of how stellar

masses are meausured. Such a conceptual understanding can be conveyed with this small

power point visualization (you must be used to these by now).

however, this level of detail is unnecessary to our conceptual understanding of how stellar

masses are meausured. Such a conceptual understanding can be conveyed with this small

power point visualization (you must be used to these by now).

One important aspect of these measurements is that the separation of the star must be measured in physical units (e.g. meters, or whatever) for an actual mass to be derived. This means that you must know the distance to the binary systems and as we just learned, that requires parallax measurements. However, since 1/2 the stars in the sky our binary stars, then the parallax sample actually does contain a lot of binaries. The other requirement, is that the each component of the binary system is sufficiently well separated so they appear as two distinct stars. In this way, the angular seperation of the stars can be well measured and if the distance is known, that angular separation can be translated into a physical distance (e.g. orbital radius) between the stars.

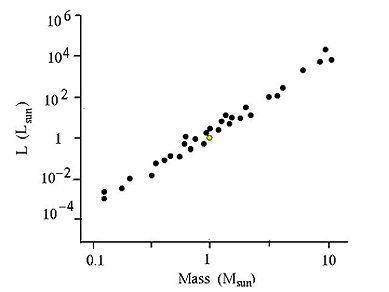

When such a sample of main sequence binary stars is measured, and the masses are plotted against the

luminosities of the those stars, one sees the following correlation known as the mass-luminosity relationship:

http://rst.gsfc.nasa.gov/Sect20/hr-diagX.jpg

The X-axis is in units of solar masses and the Y-axis is in units of solar luminosities. The position of the sun (1 solar mass, 1 solar luminosity) is indicated by the yellow dot. Clearly the trend of this relation is that more massive stars are also more luminous. That probably makes some intuitive sense as more massive stars have, in principe, more material to burn. However, it will turn out to be not so simple. In particular, the slope of the relation between stellar mass is not 1 which means the stellar luminosity is not directly proportional to stellar mass (meaning if you increased stellar mass by a factor of 10 you would increase stellar luminosity by the corresponding factor of 10).

Indeed, we have already seen a hint of this earlier in our construction and review of the HR diagram where we saw that is possible for stars to be 10,000 times more luminous or 10,000 time less luminous than the sun. If stellar luminosity was directly proporational to stellar mass, then that would mean that some stars are 10,000 times more massive than the sun and some are 10,000 times less massive than the sun. This doesn't seem likely.

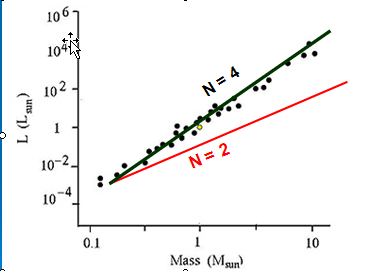

Therefore, stellar luminosity must scale as stellar mass to some power N (like we saw earlier in the scaling between stellar luminosity and surface temperature):

But what is N?

The image below shows two fits to the data; one with N=2 and one with N=4.

Clearly the N=2 fit is not good and the N=4 fit is much better (the best scaling occurs with N=3.5). The meaning of the N=4 fit is as follows: a 2 solar mass star would have 24 times more energy; a 10 solar mass star would have 104 more energy, etc,etc. Thus, empirically we have established something very important:

The luminosity of a star is a very sensitive function of its mass. Small changes in the mass produce large changes in the luminosity (total energy output) . This must be telling us something fundamental about the structure and energy sources of stars. In quantitative numbers, a star that is 10 times more massive than the sun is generating approximately 10,000 times more energy. Wow - what could cause that?